Genomic Analysis of Andean Frogs Reveals How Elevation Shapes Evolution

Published:

High in the Andes, a group of frogs reveals the secrets of how life adapts to extreme environments. In a recent study published in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, we explored the genomes of Oreobates frogs, a genus found across a remarkable range of elevations, from the Amazonian lowlands to Andean peaks exceeding 3,800 meters. Combining decades of fieldwork (1999–2016) across the challenging terrains of the Andes with cutting-edge genomics, our research decodes how mountain gradients shape biodiversity in these Neotropical frogs.

The common big-headed frog (O. quixensis, left) is one of many Oreobates species found in the Andes. The images to the right show two contrasting habitats within the genus's range: Yungas forests (top right) and highland grasslands (bottom right). Photo credits: Aaron Bloch (left), Wikipedia (top right), Unknown (bottom right).

The common big-headed frog (O. quixensis, left) is one of many Oreobates species found in the Andes. The images to the right show two contrasting habitats within the genus's range: Yungas forests (top right) and highland grasslands (bottom right). Photo credits: Aaron Bloch (left), Wikipedia (top right), Unknown (bottom right).Highland Adaptation: A Story Written in the Genome

We hypothesized that the dramatic environmental differences between highland and lowland habitats would leave distinct marks on the Oreobates genomes. Using a custom-designed genomic toolkit, we captured and analyzed nearly 18,000 exons (protein-coding regions) from 65 individuals representing 18 Oreobates species and closely related frogs.

Our findings revealed a stark contrast: highland Oreobates, adapted to fragmented habitats like puna grasslands and elfin forests, exhibit smaller effective population sizes and, crucially, a higher rate of nonsynonymous mutations (changes that alter proteins) compared to their lowland relatives. This pattern suggests that, in the highlands, stronger genetic drift (the random fluctuation of gene variants) weakens the typically “purifying” effect of natural selection, allowing a wider range of mutations to persist, potentially driving adaptation to these challenging environments. In essence, highland habitats create unique evolutionary pressures, where isolation and fluctuating climates accelerate genetic change, carving distinct evolutionary paths for montane species.

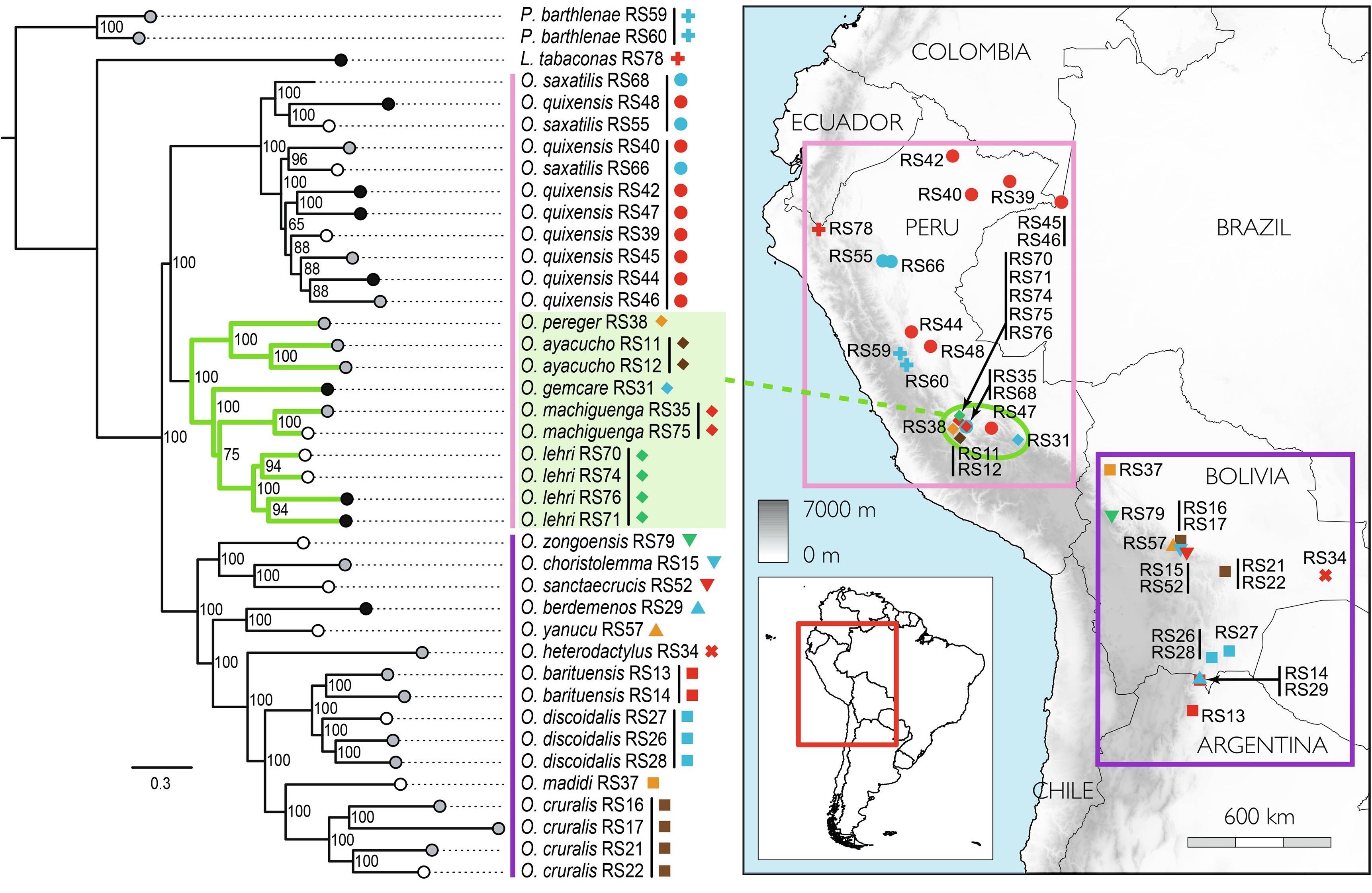

A phylogenetic tree (left) showing the relationships among Oreobates frogs. Species found in high-elevation habitats are indicated by green branches. A corresponding map (right) shows the sampling locations across the Andes. Colors on the map represent the two major Oreobates lineages: a northern group (Colombia to Peru, in pink) and a southern group (Bolivia to Argentina, in purple). Adapted from Montero-Mendieta et al., 2021 (Fig. 3).

Taxonomic Puzzles and the Power of Genomics

Our study also uncovered some surprising relationships among lowland species, challenging traditional taxonomic classifications. For example, O. quixensis and O. saxatilis, long considered distinct species, appeared intermingled in our genomic analyses. Population structure tests revealed evidence of shared ancestry. This genetic blurring could be due to a few factors, such as misidentification of some museum specimens, or ancient hybridization between the two lineages. Similarly, O. barituensis and O. discoidalis showed minimal genetic differentiation, suggesting they may, in fact, represent a single species. This shows how genomics can be a powerful lens through which to re-examine species boundaries, revealing that the lines we draw in nature are sometimes fuzzier than we thought.

Conservation in a Changing Climate

Andean amphibians face increasing threats from habitat loss, climate change, and disease. Our study highlights the particular vulnerability of highland Oreobates species. Reduced genetic diversity and small, isolated populations create an “evolutionary trap”, making them less resilient to environmental changes. Protecting, and ideally restoring, connectivity between these fragmented populations is crucial to buffer against extinction risks. Our findings also underscore the need to look beyond traditional species definitions and consider the hidden genetic diversity within and among populations. This is particularly crucial for groups like Oreobates, where some species are restricted to tiny geographic areas and have very small population sizes, making them exceptionally vulnerable.

The ‘devil-eyed’ frog (O. zongoensis, left), a critically endangered species restricted to Bolivia's Zongo Valley, and O. machiguenga (right), known only from Peru's Cordillera Vilcabamba slopes. Both highlight the conservation challenges that many Andean amphibians face, particularly those with very limited distributions. Photo credits: Steffen Reichle (left), José M. Padial (right).

A Blueprint for Future Studies

In our paper, we used a custom-designed exon-capture approach specifically for Oreobates that achieved exceptional efficiency—outperforming previous amphibian genomic studies. By systematically comparing bioinformatics pipelines, we also revealed how methodological decisions can shape evolutionary interpretations. Together, these advances provide researchers with a powerful roadmap for future evolutionary studies of non-model organisms, helping unravel how biodiversity emerges and persists in Earth's most challenging environments.

---

Publication details

Montero-Mendieta, S., De la Riva, I., Irisarri, I., Leonard, J.A., Webster, M.T., & Vilà, C. (2021). Phylogenomics and evolutionary history of Oreobates (Anura: Craugastoridae) Neotropical frogs along elevational gradients. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 161, 107167.