Highlights from SMBE 2025 in Beijing: Cavefish, Quails, and Evolution

Published:

This July was a bit different from my usual routine in Beijing. Instead of being glued to my computer, I joined over a thousand scientists for the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution (SMBE) 2025 conference. It was a milestone event—the first time this meeting has been held in China—and it felt incredible to welcome so many international colleagues to the city where I do my research.

The impressive main stage of the SMBE 2025 meeting in Beijing, setting the scene for a week of world-class science in the field of evolutionary biology.

Between the keynote speeches and the specialized sessions, I spent a lot of time learning from colleagues. The diversity of topics—from the genetics of ancient humans to the evolution of viruses—was a powerful reminder of how dynamic our field is.

Deep in thought while listening to the latest research during one of the plenary sessions.

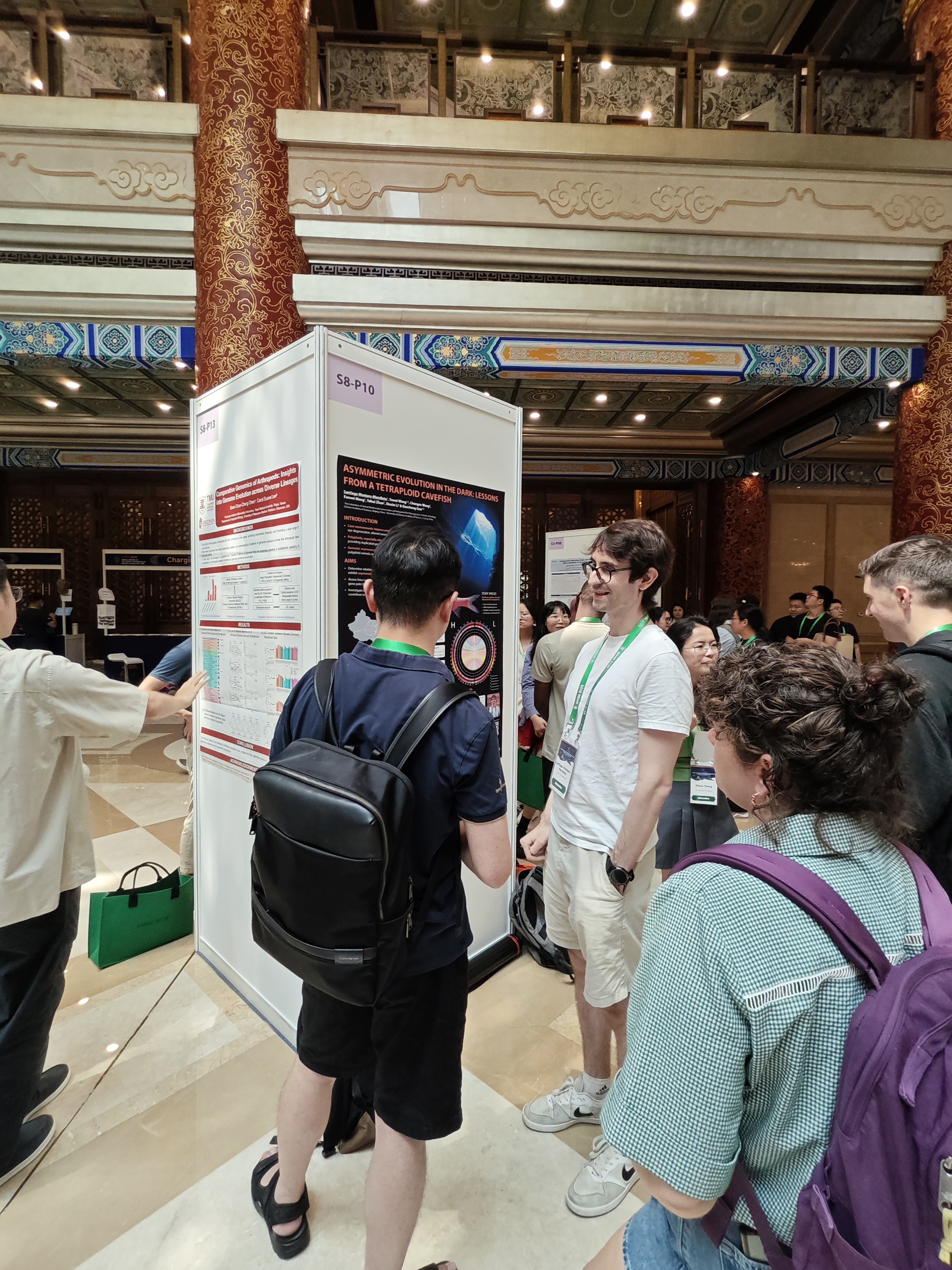

During the poster sessions, I had the chance to present my work on the genomic evolution of a tetraploid cavefish. The central question we addressed is how animals adapt to extreme environments. This cavefish is a perfect model because it has a duplicated genome—two copies of every gene—giving it a unique evolutionary toolkit to survive in complete darkness.

Our research, now published in Molecular Ecology, reveals a fascinating evolutionary strategy. We found that the two genomes evolve asymmetrically: one subgenome rapidly changes and innovates, allowing for the quick loss of useless traits like vision, while its partner acts as a stable backup, preserving essential life functions. It's a beautiful example of evolution having a safety net while taking risks.

→ View the full Cavefish Poster here

Explaining how a duplicated genome helps cavefish adapt to life in complete darkness.

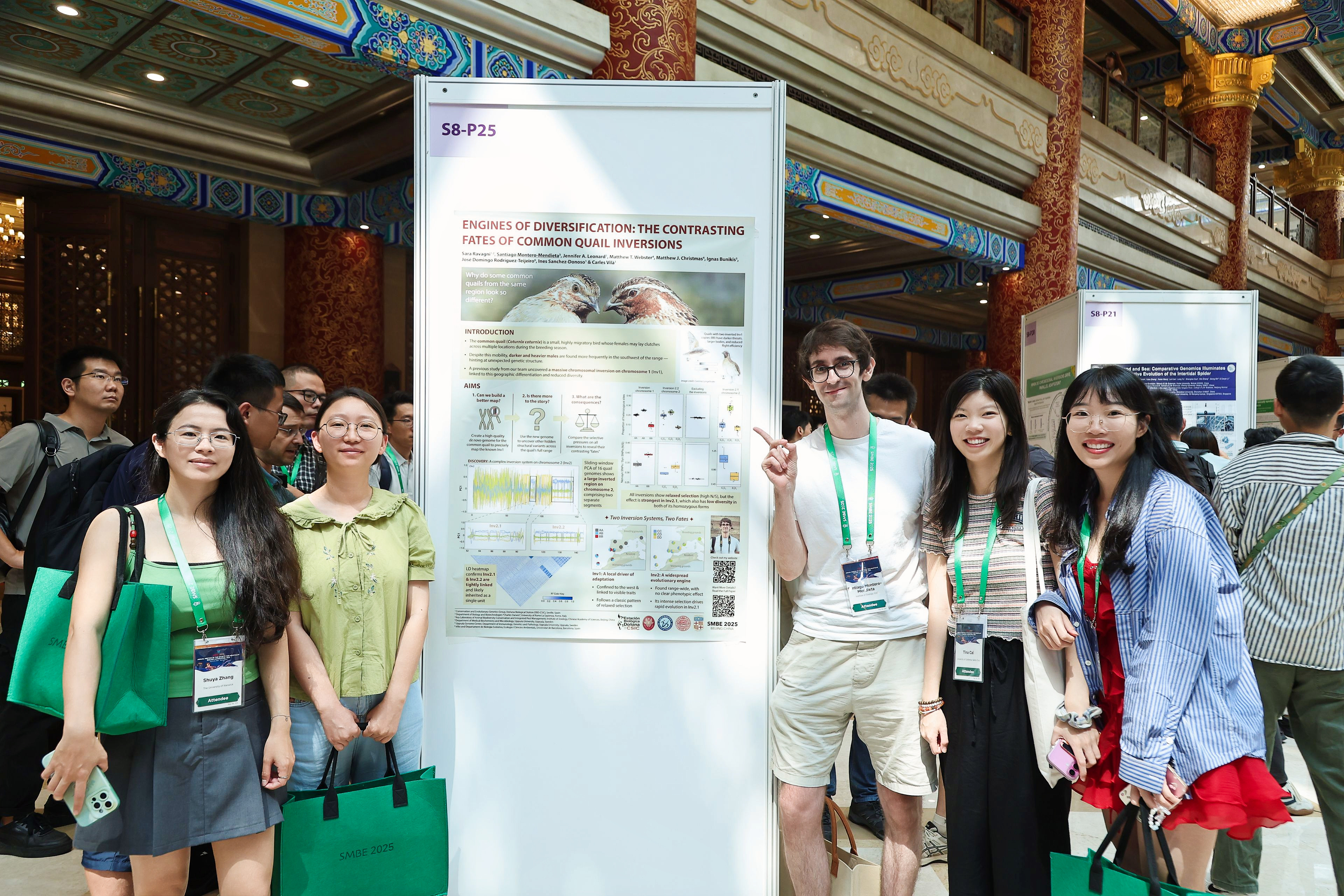

I also presented a second poster on my common quail research, which tackles a completely different kind of evolutionary mystery. Quails are highly migratory, so we'd expect their genes to be well-mixed. But they're not. We see physically distinct birds in the same regions, which led us to uncover massive 'supergenes'—huge chunks of flipped chromosomes called inversions—that drive these differences.

Our study, also recently published in Molecular Ecology, delves deeper into this phenomenon. The big surprise was discovering two different inversion systems with completely different 'fates'. One is a young, 'local' supergene that creates the darker, heavier birds in a specific region. But the other is an ancient, widespread 'engine' that generates hidden genetic diversity across the entire species and is evolving incredibly rapidly.

→ View the full Quail Poster here

It was a pleasure to discuss our findings on quail evolution with interested colleagues during the poster session.

Overall, it was a rewarding and inspiring week. Having the world of molecular evolution come to Beijing was a fantastic experience, and I’m proud to have shared my recent research discoveries at this historic first SMBE in China.